The South Carolina of Kentucky:

The Election of 1860 Part II

Written by Justin Lamb

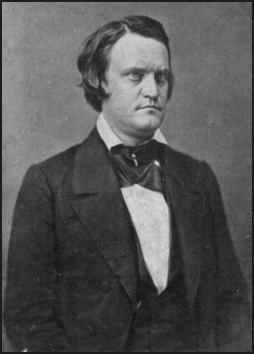

Republican Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 presidential election, but it was Southern Democrat John C. Breckinridge (above) who overwhelmingly carried the Jackson Purchase region of Kentucky.

(Courtesy of National Archives)

Slavery was a hot-button issue in the 1860 presidential election, but it wasn’t a wedge issue in Kentucky as the peculiar institution was considered the way of life and both Kentucky Unionists and States Rights Democrats wished to preserve it. The dividing issue was the preservation of the Union versus the right for a state to secede. This dividing rhetoric between the Jackson Purchase and the remainder of the state lies in the isolation the Purchase and differences in lineage. Cut off from the state by the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, the Purchase never associated with politics and way-of-life of the remainder of the state. Political influence did not come from the “Golden Triangle” of Frankfort, Lexington, or Louisville, but from the Southern cities of Nashville and Memphis.

The ancestral and cultural background of the Jackson Purchase differed from the rest of the state as well. As a whole, Kentucky did not necessarily identify as a southern state even though it was a slave state and was located below the Mason-Dixon Line. Alienated from the state by geography, politics, and cultural background, the Jackson Purchase region identified as part of the South. The Bluegrass, Green River, and Eastern mountain regions of Kentucky traced their lineage back to Virginia. In contrast, the Jackson Purchase region settlers came from mid-South and Deep Southern states such as Tennessee, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Alabama. With them they brought their southern identity, beliefs, and culture.

Kentucky’s diverse history became even more complicated as the Civil War began in 1861. Perhaps no other state experienced the division of brother against brother and neighbor against neighbor as much as Kentucky. The Commonwealth of Kentucky officially declared neutrality and eventually came to support the Union cause, but the Jackson Purchase region was an enclave of Rebel support and voted overwhelmingly for secession, and even called a convention to secede from the state of Kentucky after the General Assembly failed to leave the Union in 1861.

As the 1850s came to a close, division was deep in America with the country teetering on the brink of all out civil war. The question of how to properly deal with the issue of slavery had virtually separated the country into a sectional crisis and caused the demise of one of the major political parties (the Whigs). The national mid-term election of 1858 witnessed the newly formed anti-slavery Republican Party take control of the House of Representatives by a slim margin. Kentucky’s First Congressional District which included the Jackson Purchase, overwhelmingly re-elected Democrat Henry C. Burnett of Trigg County. Burnett was a staunch supporter of Southern interests prompting Louisville Journal editor George D. Prentice to write, “[Burnett] is a big, burly, loud-mouthed fellow who is forever raising points of order and objections to embarrass the Republicans in the House.”

Following the mid-term elections, the Republican controlled House of Representatives used their majority to successfully blocked Democratic President James Buchanan’s agenda. Buchanan, though a Northerner by birth, was sympathetic to Southern interests which put him at great odds with the Republican Party whose base was in the Northern Free States. The Buchanan presidency witnessed the Dred Scott decision where the U.S. Supreme Court overturned the Missouri Compromise, making slavery legal in all territories of the United States and the fallout of the Kansas-Nebraska Act which led to the escalation of a deadly territorial war in Kansas between anti-slavery and pro-slavery forces known as “Bleeding Kansas.” The country was at a breaking point over slavery and President Buchanan opted not seek re-election in 1860.

In April 1860, the Democratic Convention convened in Charleston, South Carolina to nominate a candidate for president. The convention soon became deadlocked over the slavery issue and a nominee could not be secured. Stephen Douglas of Illinois led the field in votes, but could not secure a majority needed for the nomination. Angry over the party platform, many delegates, mostly from Southern states, bolted the party. The Democrats reconvened in Baltimore, Maryland where they nominated Stephen Douglas on the first ballot which was possible because many Southern Democrats refused to attend. The Southern Democrats instead met in Richmond, Virginia to nominate Vice President John Breckinridge as the nominee of the Southern Democratic Party. Both Douglas and Breckinridge claimed to be the true nominee of the Democratic Party.

Abraham Lincoln, a former one-term congressman from Illinois, won the Republican Party nomination in May 1860, after the party frontrunner William Seward was seen as too polarizing to many factions of the party. The Republicans hoping to capitalize on the divisions within the Democratic Party, nominated Lincoln as the candidate who could best unify all factions of the party. The Republicans adopted a strong anti-slavery platform.

Many moderate to conservative former Whigs and Know-Nothings formed the Constitutional Union Party which nominated John Bell of Tennessee. The Constitutional Union Party, hoping to extinguish the flames of the sectional crisis and fearing civil war, offered compromise and ran on the slogan, “Union as it is, Constitution as it is.”

The prime issue of the 1860 election was the expansion of slavery into the western territories. The Northern Democrats called for the will of the people to be respected and for popular sovereignty in each territory to be the deciding factor. The Southern Democrats believed slave owners had the right to expand into the western territories and had the right to bring their property including slaves with them. The Constitutional Union Party avoided the slavery issue altogether and relied on platform of compromise and ‘hoped the sectional crisis went away on its own.’ The Republican Party platform called for a complete halt of the expansion of slavery into the western territories.

In a return to their Whig roots, a majority of Kentuckians cast their hopes behind Bell and the Constitutional Union Party. Colonel Quintus Q. Quigley, an attorney located at Paducah in the heart of the Jackson Purchase region, was a strong Bell man and served as First Congressional District Elector for the Constitutional Union Party. Quigley had been a staunch follower of the Whig Party and was confident his Whigs could have solved the sectional crisis. Quigley feared the Democrats did not have what it took to save the Union, “[The Democrats] were fat with spoils and panting yet more for food for hungry men…the frank dishonesty and corruption was enough to sicken the heart and awaken despair in the minds for the preservation by the country of such a party.” Quigley believed the Constitutional Union Party could invoked the spirit of Henry Clay and avert a civil war.

Though Quigley threw his support behind Bell, he was in the minority in his native region of the Jackson Purchase. The area which had had an independent streak since its founding, exerted its independent nature once again in the 1860 election and overwhelmingly backed the southern rights platform of the Southern Democratic Party and its candidate, John Breckinridge. The Louisville Daily Courier reported on Monday, July 9, 1860, the Democracy of Marshall County met at the Benton Courthouse where “rousing speeches and cheers of her lion-hearted democracy were given in support of Breckinridge.” The paper also reported that “Douglasism had no foothold in Marshall County.” Though a Kentuckian by birth, Lincoln had very little support in his native state, much less the Jackson Purchase region with its strong Southern ties. Lincoln’s affiliation with the “Black Republican Party,” as many in Kentucky referred to, killed his chances of any electoral gains in the Bluegrass state. Many “Fire-Eaters” within the Democratic Party threatened secession from the Union if a Lincoln victory were to happen. In a Hickman Courier editorial featured on August 2, 1860, the editor confirmed the Purchase’s loyalty to the Breckenridge ticket, “The needle is not truer to the pole than are the Democracy of Jackson’s purchase to their principles. They will come up now, in the hour of need, with a majority that will confound our enemies and astonish our friends.”

Though Breckinridge was the clear favorite in the Jackson Purchase, some Democrats were concerned that the anti-Republican vote was too split with three candidates and worried of an impending Republican victory. William George Pirtle, a Graves County farmer in the small community of Water Valley, voiced his concerns in his memoires, “If the parties opposed to the Lincoln platform would have agreed on one man, they could have elected him easily….But every man would go for his man or rather his own way.” Pirtles fears were realized as Lincoln swept the Northern Free States on his way to victory. The electoral votes of the Southern and Border States were split among Bell, Douglas, and Breckinridge thus allowing Lincoln to win the presidency. Kentucky was carried by Bell who carried the state by 45 percent of the vote. Bell won majorities in every region of the state except the Jackson Purchase which went for Breckinridge. However, Bell was able to carry the counties of Ballard and McCracken Counties, and he narrowly lost Fulton by one percentage point. Breckinridge carried large majorities in Calloway, Graves, and Hickman. Marshall County cast the largest majority for Breckinridge at 73.8 percent of the vote. Lincoln’s unpopularity in Kentucky showed clearly on Election Day as he carried only 1,364 votes statewide. He fared worse in the Jackson Purchase where only 10 votes were received. Marshall County, located in the heart of the Purchase, gave Lincoln zero votes. Historian Berry Craig best summed up the 1860 presidential election in the Purchase in his book, Kentucky Confederates when he wrote, “Purchase politics was more like Deep South politicians than Kentucky politics. The region leaned decidedly toward Breckinridge, though Bell seemed to have significant support in traditionally Whig McCracken County, or at least Paducah. Douglas looked like an also-ran, and Lincoln partisans could be counted on one hand, maybe two.”