The South Carolina of Kentucky:

The Jackson Purchase Loyalty to the Confederacy

Part 1

Written by Justin Lamb

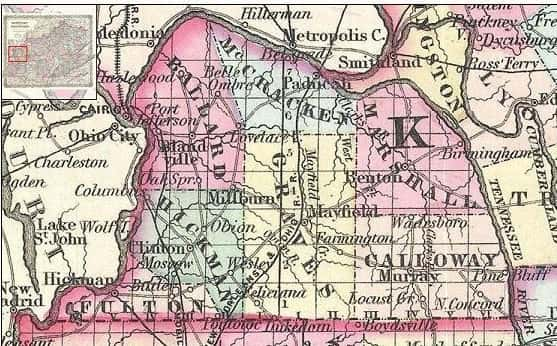

1858 map of the Jackson Purchase region

(Courtesy of Kentucky State Archives)

“The time has come…the hour has arrived…we are determined to rush to the rescue of our country…We want to kill a Yankee…never can sleep sound again until we do kill Yankee.” The written words of Edward I. Bullock unabashedly expressed his fire-eating and strong pro-secessionist views which reflected the majority of his peers in the Jackson Purchase region of Kentucky. Bullock was a wealthy lawyer in Hickman County located along the Mississippi River, and by the winter of 1860, he began publishing the Daily Confederate News and was fervently rallying for a Kentucky exit from the Union.

As the country became severely divided over the sectional crisis, the Purchase area of Kentucky longed for secession and some were anxious for a war of independence from the Union. “True we don’t want war in Kentucky,” wrote the ghost writer F.M.C in the Olive community of Marshall County during the summer of 1860, “But some things can be worse than war, and in my judgement, it would be worse to forfeit our honor and help pay men to exterminate our brothers in the South.” As Kentucky became increasingly more Unionist, the Jackson Purchase stubbornly held to its Rebel identity prompting many to nickname the region the “South Carolina of Kentucky.”

The people of the Jackson Purchase region have always been independent by nature. This could be attributed to their frontier heritage and the geographic isolation and the perceived neglect the region endures from the rest of the state. Cut off by the Tennessee River, the Purchase has often been ignored by its brethren to the east. Even in books written about the history of Kentucky, researchers are often frustrated as the historians mainly focus on the Bluegrass Region, home to the state capital of Frankfort, or the mountains of Eastern Kentucky, thus ignoring the bottomlands of the Jackson Purchase. Several books have been written about the history of Kentucky, but it is only in the 1885 book Kentucky: A History of the State by W.H. Perrin, J.H. Battle, and Kniffin where the history of the Jackson Purchase region is given much attention, and even so, not much is told about the region in this publication. Perhaps lack of records or a complete disregard for the region are to blame. Perrin, et.al. noted this stepchild status of the Purchase region when they wrote “the citizens of the Purchase were placed at a serious disadvantage in respect to their proper rights and privileges under the state government.”

Unlike the rolling fertile hills of the Bluegrass and Green River regions, the Jackson Purchase was the last area of Kentucky to be settled, and was for many years, avoided because of its unappealing land. According to noted western Kentucky historian Berry Craig, much of the interior land of the Jackson Purchase region was prairie land devoid of any valuable timber. “The land varied from cottonwood and sycamore studded floodplains along the big rivers to low, rolling hills and littler valleys bisected by small, shallow, meandering creeks that all but dried up in summer.” For the culturally and economically disadvantaged, the Jackson Purchase became a poor man’s paradise due to its cheap land prices.

Many historians have suggested that poor settlers were pushed out of the Bluegrass Region by the wealthy elite in order to lay claim to the best lands and in an effort to control production in the state. Many poor whites had to compete with slaves for jobs and finally moved westward into the unchartered territory of the Jackson Purchase. “By pushing the poor farther and farther west, elites were able to control the means of economic production and solidify their hold on Kentucky politics.”

In the years leading up to the Civil War, politics in the Commonwealth of Kentucky was dominated by Henry Clay and the Whig Party. Clay cast a large presence on the nation as he climbed the rungs of the political ladder serving as Speaker of the House, Secretary of State, United States Senator, and a three-time presidential candidate. Clay’s career is best remembered for keeping the Union enact on two important legislative compromises: the Missouri Compromise and the Compromise of 1850. Clay’s prominence in national affairs dominated the political situation in his native state and the Whig Party controlled every section of the Commonwealth except the Jackson Purchase region. Under the guidance of Clay’s influence, the Whig Party dominated every aspect of Kentucky politics from the 1830s until the 1850s and elected seven straight Whig governors.

The Jackson Purchase always had an independent streak especially in politics and shied away from the Whig politics that dominated the rest of the state. The hero of the Jackson Purchase was not Henry Clay, but instead was none other than the region’s namesake and Clay’s arch political nemesis, Andrew Jackson who won fame in the Battle of New Orleans during the War of 1812. Jackson was dubbed the “hero of the common man” and was later elected President of the United States in 1828 as “hero of the common man” Jackson’s election marked a turning point in American politics as he became the first frontiersman president in an election that expanded suffrage to poor white males. Henry Clay’s nationalist view of government was in direct competition to Jackson’s philosophy of a more conservative interpretation of the Constitution which championed states’ rights

Clay and Jackson were opponents in the 1824 Presidential Election which also included John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts and William Crawford of Georgia. Jackson received a plurality of the popular and electoral votes, but he did not receive the majority 131 electoral votes needed to be elected. The election was thrown into the House of Representatives as outlined in the Twelfth Amendment Constitution and came down to Jackson and Adams as Crawford and Clay were eliminated for not receiving enough votes. However, Henry Clay who was Speaker of the House of Representatives played a powerful role in selecting the next president. Adams shared Clay’s view of an active federal government and Clay threw his support behind Adams who was chosen as the next president of the United States. Jackson, who believed he would be chosen because of the plurality of votes he received, was furious. When Clay was selected as Secretary of State, which was seen as a stepping stone position to the presidency, after Adams victory, Jackson’s hatred for Clay intensified. Jackson branded the appointment of Clay as a “corrupt bargain” which fueled his rhetoric for a second presidential campaign in 1828 in which he won in a landslide.

In both the 1824 and 1828 elections, Henry Clay carried his native state of Kentucky and won every region except the Jackson Purchase which went to Jackson by 73 percent of the votes cast.1 Kentucky would be won by the Whig presidential candidate in every election leading up to the Civil War. In a move of stubborn political independence, the Jackson Purchase would put their votes and trust in the Democratic nominee. However, McCracken County which had come to rely on business and commerce interests in Paducah, became an enclave of the Whig Party and the county was carried by the Whig nominees William Henry Harrison in 1836 and 1842, Henry Clay in 1844, and Zachary Taylor in 1848. McCracken Counties Whig dominance began to wane by 1852 when it went with its sister Purchase counties for Democrat Franklin Piece, the hero of the Mexican-American War. Pierce lost the state of Kentucky. Pierce was a staunch supporter of the Fugitive Slave Act and the Compromise of 1850, which was brokered by Henry Clay and set to defuse the growing tension between the North and South over the question of slavery.

Just four years before the beginning of the Civil War, the Whig Party eventually collapsed under the weight of the slavery issue after passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act divided the party. Many conservative Whigs mostly from the South joined the Democratic Party or jumped to the short-lived American “Know-Nothing” Party which based a platform around anti-Catholic and anti-immigrant sentiments. More of the liberal Northern members of the defunct Whig Party joined the ranks of the newly formed Republican Party which was founded by anti-slavery activists and abolitionists. Whigs were divided over the question of slavery with Northern Whigs calling for a gradual abolition while more conservative southern Whigs remained pro-slavery thus leading to a split within the party. At the first Republican National Convention in 1856, the party adopted an anti-slavery platform which called for immediate abolition and Democrats charged that a Republican victory would lead to civil war. As the Whig Party faded into the obscurity of history and the Republican Party began its rise, Democratic nominee James Buchanan carried the state of Kentucky with 52 percent of the vote in the 1856 presidential election as he sailed to a national victory. The Jackson Purchase area voted overwhelmingly for Buchanan and Marshall County had the recognition of having the highest Democratic majority of any county in the First Congressional District. Interestingly, despite Democratic gains in 1852, McCracken County went back to its old Whig roots in 1856 giving former Whig president Millard Fillmore, the nominee of the American “Know-Nothing” Party, a majority of the votes cast. After nearly two decades of Whig control, the Democratic Party began a rise to political dominance in the Commonwealth of Kentucky by 1860, but only by default. Kentucky was faithful to the Whig Party, and after its collapse, Whig members found refuge in the Democratic Party or the Know Nothing Party. As the Know-Nothing Party, the last remnants of the Whig Party, faded away, the Democratic Party controlled both houses of the Kentucky General Assembly in 1860 and Democrat Beriah Magoffin was elected governor of Kentucky in 1859. The Jackson Purchase region, already a conclave of Democratic support, became increasingly more loyal to the Democratic Party as the 1860 presidential election drew near, and when the War Between the States would arrive in 1861, region would once again exert its independent nature and charter its own course.