The Mysterious Disapperance of

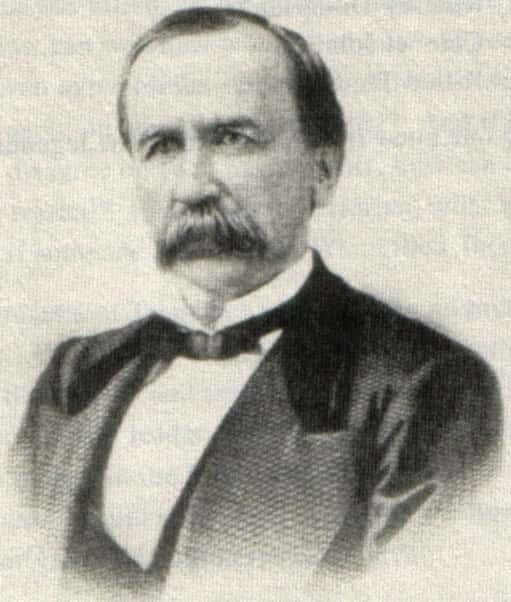

Kentucky State Treasurer James “Honest Dick” Tate

Written by Justin D. Lamb

(Kentucky Historical Society)

On March 14, 1888, Kentucky State Treasurer James Tate boarded a train in Louisville bound for Cincinnati. The man known as “Honest Dick” was never seen or heard from again.

Born in Franklin County, Kentucky in 1831, Tate’s entrance in politics came in 1854 when Governor Lazrus W. Powell appointed Tate as Assistant Secretary of State, a position he eventually held under two Democratic governors. Tate was elected Kentucky State Treasurer on the Democratic ticket in 1866 and served for the next two decades where he gained a reputation as a trusted official which earned him the nickname, “Honest Dick.”

However, not everyone was convinced of Tate’s honest reputation, and in the gubernatorial race of 1887, Republican candidate William O. Bradley called for the need to examine and audit the state treasury which had been under Tate’s rule for twenty years. Bradley lost the governor’s race that year, but his call for the audit gained momentum in the General Assembly where more lawmakers began voicing their support for a commission to examine the state treasury in late 1887. Tate told members of the legislature that he would cooperate with the audit but he needed proper time to get his books in order and the establishment of the commission was put on hold.

In early 1888, the General Assembly gave Tate notice that an audit was to move forward. Tate began a pattern of behavior that should have aroused the suspicion of officials, but his reputation as an honest official left many in State Treasurer’s office unconcerned. Tate began depositing only checks in the state’s bank accounts, instead of cash, which had been the normal practice and he suddenly began paying off a number of personal debts.

On the morning of March 14, 1888, one of Tate’s clerks, Henry Murray, noticed Tate filling two tobacco sacks full of 4 inch roll of bills and gold and silver coins that totaled near $100,000. Moments later, Tate left a note on his desk stating that he was going Louisville for business and would return in a few days. Nobody questioned any of Tate’s actions and it was only after a week passed with no word from Tate that suspicions began to arise.

An investigation ensued and it was discovered that Tate arrived in Louisville and then boarded a train for Cincinnati before vanishing forever. The state ledger books were audited and were nearly illegible. It was discovered that Tate had given several lawmakers loans that were never repaid and advances were given on salaries including several thousand dollars to Governor Preston H. Leslie in 1872. According to a 1992 article by John E. Kleber in the Kentucky Encyclopedia, Tate used some of the state’s money to make personal investments in mines and real estate. Governor Simon B. Buckner announced that Tate had misappropriated nearly $250,000 from the state treasury and he “suspended” him from office.

The General Assembly quickly moved through impeachment hearings and Tate was officially removed from office. A $5,000 reward was offered for the whereabouts of Tate, but he was never found. Tate’s wife and daughter, whom he had left behind, first claimed to have never again heard a word from him again and they told officials that they believed he had committed suicide. However, years later, Tate’s daughter admitted that he had written letters to her and the letters were postmarked from San Francisco, Canada, Japan, and China. Another witness claimed to have seen a letter that was written in 1890 to one of Tate’s closest friends postmarked from Brazil.

The aftermath of the Tate scandal became a rallying cry for reformers who called for a change in Kentucky government. A constitutional convention was held in 1891 to draft a new constitution in Kentucky. Many delegates at the constitutional convention, including Dr. Samuel Graham of Briensburg who was chosen to represent Marshall and Lyon Counties at the convention, believed Tate had served way too long as Kentucky State Treasurer which had easily allowed him to get away with such a crime. The constitution was passed which placed term limits on state constitutional officers in hopes of curbing corruption in state government.

As years passed, the whereabouts of Tate was still puzzling, but Tate continued to influence politics in Kentucky. “Tateism” became synonymous with political corruption, and in 1895, William O. Bradley, who first called for the audit of Tate’s books, was elected Kentucky’s first Republican governor due in part to the aftermath of the Tate scandal.