“Hero of the Common Man”

Andrew Jackson

Written by Justin D. Lamb

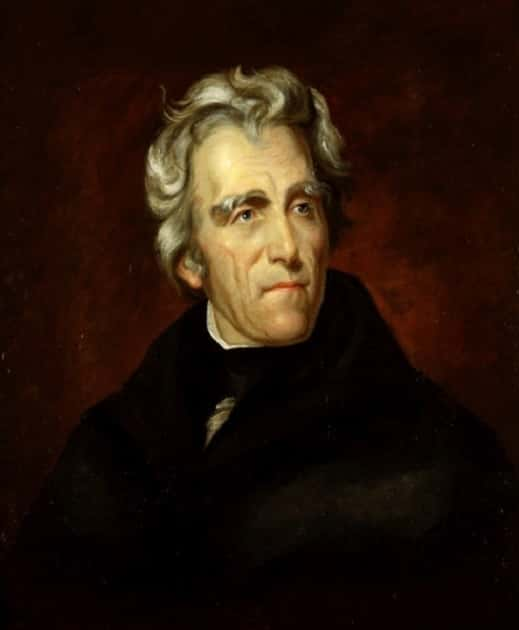

Painting of Andrew Jackson by Thomas Sully.

(Courtesy of National Archives, Public Domain)

Though Marshall County was named in honor of Chief Justice John Marshall, a leader of the Federalist Party, it was Andrew Jackson, champion of the common man and founder of the Democratic Party, who was most loved and revered in this area of western Kentucky during the early to mid-1800s. The Jackson Purchase region consisting of Marshall, Calloway, Ballard, Carlisle, Hickman, Graves, Fulton, and McCracken Counties was named in the honor of Jackson who along with former Kentucky Governor Isaac Shelby helped secure the purchase of the land from the Chickasaw tribe in 1818.

Cutoff from the rest of the state by the Tennessee and Cumberland Rivers, residents of the Jackson Purchase felt alienated and did not identify with the rich planters and aristocracy of the Bluegrass Region. Though the Whig Party led by Kentuckian Henry Clay was dominate in Kentucky politics at the time, voters in the Jackson Purchase followed Andrew Jackson and his Democratic Party.

Andrew Jackson came to national fame as war hero during the War of 1812 due to his command of American troops during the Battle of New Orleans where he gained the nickname “Old Hickory” in reference to his tough persona. With American troops outnumbered, General Jackson led them to a miraculous victory which ultimately caused the British to withdraw from New Orleans. Many of Jackson’s troops called Kentucky and Tennessee home. One volunteer solider, Moses Lovett of Maury County, Tennessee, fought with General Jackson at the Battle of New Orleans and when Marshall County was founded in 1842, his children purchased land along Jonathan Creek. Their descendants are still residents of the county today.

Following the war, Jackson became active in politics which saw him being elected to the United States Senate from Tennessee. Since he had little education and was not from a distinguished family, Jackson had to work hard to be recognized for his own merits. This helped shape his political beliefs and he spent his entire career fighting against the establishment. Jackson soon became a political rival of Senator Henry Clay of Kentucky, a seasoned politician and leader of the Whig Party. By the 1824 Presidential Election, Clay was considered the next in line to succeed President James Monroe. Two other Eastern establishment candidates, John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts and William Crawford of Georgia also joined the race. A political outsider, Jackson jumped into the race and became “a champion of the common man.”

On Election Day, the race was extremely close and electoral votes were split four ways with no candidate gaining a majority. Jackson received a plurality of the votes with John Quincy Adams coming in second place. The race was thrown into the House of Representatives who chose Adams as the winner following what Jackson supporters called a “corrupt bargain” between Adams and Clay. Clay forged an alliance and secured the votes necessary for Adams to be named president. In return, Adams appointed Clay as Secretary of State. Jackson and Clay became bitter enemies for the remainder of their lives.

Furious Jackson supporters saw the Adams-Clay alliance as a crooked and denounced the robbing of the election from Jackson in favor of the “corrupt Eastern elites.” This anger constituted into political support for Jackson which led to the creation of the Democratic Party, and in 1828, through skillful organization, Andrew Jackson was elected President of the United States in a landslide. A true man of the people, Jackson’s inaugural ball was the first to be opened to the general public. The crowd of nearly 20,000, which not only consisted of the usual political figures, but also common laborers and the poor who wished to meet and shake the hand of a president who identified with them, filled the White House.

As the booze flowed and the attendees became drunker, the party became wild as decorative dishes and antique piece were broken. Some guests stood with their muddy boots on the antique furniture in order to catch a glimpse of “their President” while others jumped out the windows of the White House. In attempt to draw the partygoers outside, White House servants placed bathtubs on the lawn filled with whiskey and booze. Author Margaret Smith who attended the inaugural ball described the scene best when she said “It was the People’s day, and the People’s President, and the People would rule.” The Age of Andrew Jackson had begun.

As President, Andrew Jackson set out to change the course of the nation. His first act was the Indian Removal Act which called for the forcible relocation of thousands of indigenous peoples from their native homes to make more room for white settlers. The act remains a controversial part of the Jackson legacy. Some Indian tribes confronted Federal officials with violence force, while the Cherokee nation of Georgia took the U.S. Government to court which resulted in the United States Supreme Court decision led by Chief Justice John Marshall ruling against President Jackson stating that he could not impose federal law on Cherokee tribal lands. Jackson seemed unbothered by the ruling and is quoted as saying, “John Marshall has made his ruling. Now let him enforce it.”

Although a staunch defender of limited government, Jackson cemented his support for a strong Union and rejected secession during the Nullification Crisis when the state of South Carolina threatened to declare void or nullify the tariff legislation of 1828. The nullification movement in South Carolina was led by none other than Jackson’s own Vice President, John C. Calhoun. Although Jackson sympathized with the South over the tariff issue, he believed it was his duty as President to keep the Union intact and to enforce Federal law. The issue came to a climax when President Jackson, known for his furious temper, threatened to send troops to South Carolina to enforce the tariff law and to hang Calhoun and the other nullifiers himself. Cooler heads prevailed as South Carolina backed down and Jackson helped renegotiate a new tariff law.

The greatest fight of the Jackson Presidency was the banking war which began in the summer of 1832 when Congress led by Speaker of the House and old Jackson rival Henry Clay passed the re-charter bill of the Bank of the United States. With aspirations to run for President that in the autumn of 1832, and being supported by the president of the Bank of the United States Nicholas Biddle, Clay pushed the re-charter through Congress. Clay presented the re-charter bill to President Jackson in an effort to force him to sign it into law. Clay believed if Jackson vetoed the bill it would crush the President’s hopes for re-election. Never to be intimidated and always his best when he had a fight, Jackson refused to sign and set out on a crusade to kill the charter. Jackson was always prepared for a fight. “I was born for a storm and a calm does not suit me,” Jackson said as he took his case against the Bank of the United States to the people and argued that the bank was a corrupt institution and benefited only the wealthy and elites. “It is too be regretted that the rich and powerful too often bend the acts of government to their own selfish purposes,” Jackson argued. The people sided with Jackson and re-elected him overwhelmingly against Clay. With a mandate from the people, Jackson successfully killed the Bank of the United States charter during his second term.

Jackson left office after two terms in 1837 and returned to his plantation, The Hermitage, in Nashville, Tennessee. In retirement, Jackson remained active in politics and continued to fight for the interests of the common men of the nation through the Democratic Party. Upon leaving the presidency, Jackson admitted that he had but two regrets “that he had been unable to shoot Henry Clay and didn’t get to hang John C. Calhoun.”

Jackson had suffered from poor health since his younger days when he received a bullet just inches near his heart after fighting a duel with Charles Dickinson, a Nashville planter, who had insulted his wife, Rachel. Jackson killed Dickinson in the duel and narrowly escaped death himself. Jackson carried Dickinson’s bullet in his chest for the remainder of his life.

Jackson remained a hero in the South especially in Tennessee and Kentucky. During the War of 1812, Kentucky sent approximately 2,300 militia men to back Jackson during the Battle of New Orleans. Despite hating Kentucky’s leading politician, Henry Clay, Jackson had a deep admiration for Kentucky and is quoted as saying, “I never in my life seen a Kentuckian who didn’t have a gun, a pack of cards, and a jug of whiskey.”

On June 8, 1845, Andrew Jackson passed away at his home in Nashville at age 78 of heart failure. Upon hearing of his death, the Boon Lick Times reported, “General Jackson died at the Hermitage on Sunday. When the messenger finally came, the old soldier, patriot, and Christian was looking out for his approach. He is gone, but his memory lives and will continue to live.”