The Hanging of Willie DeBoe

Written by Justin D. Lamb

(Courtesy of Hazel Robertson, Salem, KY)

On May 16, 1934, Willie DeBoe and Ezra Davenport drifted into Livingston County, Kentucky. The two men had been in trouble in Arkansas for a few petty crimes and now were on the run from the law. They came to the house of a Livingston County merchant, Mr. Johnson, and knocked on his door asking for help. DeBoe and Davenport told the Johnson that they were out of gas and asked if he would open his nearby rural store up to allow them to refuel. The merchant did not recognize the two men and was hesitant at first, but after a conversation with the smooth talking DeBoe, he decided to take the men to his store.

After the Johnson opened up his store, DeBoe and Davenport pulled out a gun and robbed the store taking merchandise off the shelves. Following the robbery, DeBoe and Davenport forced Johnson to return to back to his house where they demanded supper. The two men rummaged the house searching for money where all was found was a Sunday school collection. “Pocket the money,” Davenport said. However, DeBoe refused to take the church money telling Davenport that he was raised by a “good Christian mother.” Not satisfied with their plunder, Davenport forced the merchant back to his store to rob more goods and left DeBoe at the house with the merchant’s pregnant wife and two children.

While Davenport was gone with the merchant, DeBoe assaulted and raped the merchant’s wife while her two children cried for her in the next room. Davenport soon returned and picked up DeBoe as they escaped in the merchant’s car which was later found abandoned in Lyon County. Livingston County Sheriff George Heater was contacted by the victimized merchant and a manhunt was organized for DeBoe and Davenport.

A week later, a farmer in Lyon County reported to local officials that he was robbed by two men while his wife was attacked and that the two men took off in his car heading south. On June 2, an elderly woman in Bogota, Tennessee was found brutally beaten in her grocery store, and a few hours later, DeBoe and Davenport were arrested and lodged in the Dyersburg jail. Officials in Livingston County were contacted and Sheriff Heater, Commonwealth Attorney Alvin Lisenby, and the Johnson and his wife made the trip to Bogota to identify DeBoe and Davenport.

Three days later a violent mob raided the Dyersburg jail looking to take the law into their own hands and bring vigilante justice to DeBoe and Davenport. Officials covered the two prisoners in sheets and whisked them down to Memphis for safe keeping until a trial could be held. Soon after, Livingston County Circuit Judge Charles H. Wilson called a special session of Circuit Court and the two men were eventually indicted. Davenport was indicted on three counts of robbery and two counts of aiding and abetting while DeBoe was charged with three counts of robbery, two counts of assault, and rape. The men were extradited back to Kentucky to await trial and kept in the Eddyville Penitentiary.

The trial generated a great sensation throughout western Kentucky as hundreds of people from all parts of Kentucky made the journey to Smithland to watch the events unfold. DeBoe was tried first on July 19th and he pleaded not guilty. The merchant’s wife was called to testify and gave a detailed description of the alleged assault and rape. DeBoe’s fate was handed over to the jury, and after a five minute deliberation, he found guilty and sentenced to death by hanging. Davenport was tried the next and found guilty and sentenced to 27 years for the robberies and 20 years for aiding in the attack.

DeBoe’s attorney filed an appeal which was not heard until February 1935 where the court decided to uphold the verdict. DeBoe’s execution was set for Good Friday, April 19, 1935 and DeBoe was kept out of Livingston County for safe keeping. Sheriff Heater contacted a Mr. Hanna of Epworth, Illinois who was an expert at constructing gallows at the Livingston County Courthouse.

While the gallows were being constructed to execute her brother, 19-year old Margaret DeBoe made the trip to Frankfort to see Governor Ruby Laffoon to plea for her brother’s life. Governor Laffoon responded “there is nothing I can do for your brother” and sent her on her way.

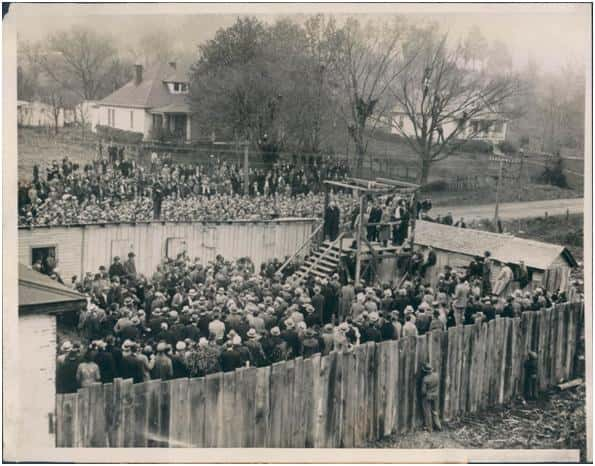

At 2:30am on April 19, Willie DeBoe was brought into Smithland to be put to death and the crowds had already begun to gather to witness the execution. It was reported the crowd by early morning was extremely large and estimated in the thousands. Sheriff Heater deputized many special deputies in order to keep law and order and to ensure the execution went as planned. Immediately before the designated hour, officials were seen applying castile soap and powder to the knot of the noose for easy slipping.

DeBoe’s sister and father were allowed one last visit and a breakfast of ham, eggs, and coffee was ordered for them. Newspaper reporters from all across the nation picked up on the story and were present in Smithland on that day. Reporters Henry Ward and Edwin J. Paxton with the Paducah Sun-Democrat and Dillard Stokes of the Associated Press were granted brief interviews with the condemned man. DeBoe told the reporters “They all think I’ll weaken when I stand on that trap. No, not Willie DeBoe! They don’t know me if that’s what they say because ole Willie DeBoe is going down a-swinging!”

DeBoe was then read his death warrant and before making the 13 steps up the gallows, he told his father and sister, “Brace up, it is not as bad as you think.” DeBoe walked up the gallows with the sheriff and a deputy and was asked if he had any last words. DeBoe then began a 45 minute tirade where he thanked the officers for treating him well, but condemned the victims of the crime. The Paducah Sun-Democrat reported DeBoe’s scathing speech:

“Is Mrs. Johnson here?” DeBoe asked. An almost oppressive hush falls and every eye is on the tall, black haired man of 22. Hundreds notice the black straps that grip his arms and legs. But most of all, they notice no tremor in his voice. “Is Mrs. Johnson here,” DeBoe repeated. “See, she wouldn’t come, she wouldn’t come.”

“Yes she is here!” answered a voice from the back of the crowd which was soon identified as Mr. Johnson the merchant and husband of the rape victim. DeBoe soon spots Mrs. Johnson and with effort, he brings up his cuffed, strapped arms a triffle seeking to level them at the woman. He cries almost bitterly, “Well, Mrs. Johnson, are you happy that I am here?!” The hush deepens. The woman pales and stares at the man who stands on the steel trap. “Talk to me Mrs. Johnson!” DeBoe demanded. “Ha, she won’t talk. Look at her everybody. She’s as pale as a corpse. She’s more afraid of this than I am. Well, she ought to be. She is sending me to my death for something I didn’t do.” Many of those present were astonished, some flabbergasted, other disgusted at DeBoe.

After his long rant, DeBoe smiled broadly before the black hood and noose was placed over his head. DeBoe’s sister, Margaret fainted, as the hood came down over her brother. The noose was adjusted tightly with the knot being place over his left ear. The sheriff nodded his head and the trap door was opened and a big thud was heard as DeBoe swung. His feet splashed into a pit that was dug and filled with water just below the scaffold. After 11 minutes, DeBoe was pronounced dead at 6:46am by Dr. W.T. Little of Calvert City and Dr. Malcolm Dunn of Smithland. DeBoe was the first white man to die under Kentucky’s law which made rape and offense punishable by hanging. The hanging of Willie DeBoe was one of the very last legal hangings in the United States. DeBoe’s body was taken to Paducah where he was buried in Oak Grove Cemetery.